Transcribing the memories of people who had experienced World War Two made me realise that I too was alive at that time, living with my family in Cheshire. I was born a year before the war started but had begun to attend full-time school before the war was over and so was old enough to remember some of the events of that time. In school, paper was in short supply so we were allowed one sheet of Izal toilet paper if we needed to go to the outdoor toilets across the school yard. To practise writing and maths we had small slates and chalk with a thick wad of felt for erasing the work.

At the beginning of the war before my memories started, my parents had an evacuee family living with them. This was an experience my mother did not enjoy and she was relieved when they were given accommodation nearer to where they came from. I was a toddler and it became too much for her to have others in the house.

One of my earliest memories was of my uncle coming to visit us, often bearing gifts from Canada. He had emigrated to Canada as a baby with his mother in 1920, leaving behind my mother and her sister to be brought up by grandparents. He came over as a member of the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) and surprised us with a visit. I have since discovered what ‘painting the town red’ means; at the time I didn’t understand what it meant in regard to my uncle!

On one occasion he came back from a visit to Canada with a suitcase full of peanut butter. It was delicious on sandwiches with homemade jam especially blackberry jelly which my mother made from the berries we picked in the hedgerows.

My uncle, Flight Lieutenant Arthur Edwards, joined the RCAF in 1940 and began aircrew training in Canada. He later joined an overcrowded transport ship and landed in Liverpool before being transferred in a sealed train to Bournemouth for further training. After being transferred to the Royal Air Force station at East Fortune in Scotland [now home to the National Museum of Flight], he learnt to fly firstly Bristol Blenheim aircraft and then Bristol Beaufighter Mark IIs. Following completion of his training he was transferred to No. 404 Squadron of the RCAF, which was then flying bombers from RAF Chivenor in north Devon to hunt German submarines in the Bay of Biscay. After a time here he was transferred to No. 236 Squadron at RAF North Coates in Lincolnshire where he searched for German convoys bringing Swedish iron ore along the Norwegian coast.

On one occasion early in 1944 my uncle was leading an aircraft section in a diving attack on a German escort ship when a 20 mm shell hit the aircraft’s armoured windscreen leaving it totally opaque, while another hit a propeller blade making it necessary to shut down the starboard engine. His Spitfire escort lost him so it was necessary for him to fly home alone at low level without being able to see forward. He decided during the next hour that if he ever got the aircraft back to base and on the ground in one piece, then nothing that could ever happen after that would be worth worrying about. He landed safely but soon afterwards he was taking off for a training mission when an engine failed and he hit a sea wall at the end of the runway and found himself in hospital for six months. At the end of the war he was repatriated to Canada and I didn’t see him again until he came back for a reunion of his squadron some years later.

One of the good aspects of having a grandmother in Canada was that she sent over food parcels during the war and for a time afterwards. I disliked the chocolate she sent, but loved the packets of nuts. Butter was in a sealed tin and there was often a tin of Klim (dried milk) – the name comes from ‘milk’ spelt backwards. She made her own soap and included this in the parcel. It was a rather special soap as it floated in the bath. The parcel was wrapped in white cloth and sewn on. On arrival this was carefully unpicked and the material used for tea towels and such like.

Although my father was in a reserved occupation, wartime must have been exhausting for him. He was an air raid warden, had an allotment, helped on his parents’ farm and had a full day’s work to do. Often at night he would collect vehicles from Manchester to be converted into ambulances at the factory where he was the foreman. He told me he tried to drive on the tramlines as far as he could out of Manchester to get a smoother ride.

With the possibility of being bombed by the Germans, my father and our neighbour built an air raid shelter in the back garden. This was very well built and provided shelter for both families. My mother used to struggle down with me in a crib type gas mask until I was old enough to have a Mickey Mouse mask of my own.

The area where we lived had quite a lot of industry but fortunately very few bombs dropped anywhere nearby. The German bombers would fly overhead to Manchester and Liverpool, and I can remember seeing search lights, in the distance, over these towns. Crewe was nearby and the railway works had barrage balloons over it. The walls of the building were painted to look like rows of houses and it escaped destruction during the war. The nearby Foden’s motor works produced tanks and these used to be tested on a field at the end of the road we lived in. This was always called the ‘’tank field’ until houses were built on it after the war.

As time went by and the villagers realised that the Germans weren’t particularly interested in them, air raid shelters tended to be no longer used. A film now in the National Archives was taken of children at my primary school going into the school’s air raid shelters during the war, also lining up books in the playground when there was a book collection in aid of the war effort. The filming took place just before I started school and I was always disappointed I was never allowed to see inside the shelters.

Because my father’s parents had a farm we were able to have some extra food from there which helped immensely. Every Christmas my father would put me on the front of his bicycle and go with my mother on her bike to the farm for a Christmas meal. He had made a wooden saddle to fit on the cross bar of his bicycle which I would use until I could ride a bike of my own. One year my uncle had fattened a turkey for Christmas but when it came time to kill it, they couldn’t because it had become a family pet.

I think we managed to go on holiday every year as we were able to use a caravan that was parked at Llanddulas in North Wales. My father had made the caravan for his boss and so was able to use it when no-one else needed it. We would travel by train to Abergele, having sent our luggage off in a big trunk in advance. My father only had one week’s paid holiday but my mother and I would stay for longer. I remember seeing the large concrete obstacles on the beach to prevent the enemy from landing.

On several occasions my mother took me to Chippenham where her sister and her children lived. My main memory of Bristol station was that it was where I swallowed a plum stone! I also remember the train stopping frequently when air raids were taking place over that city. I used to get bored and tried pressing buttons on the blinds to get the train to move. The trains, like houses, had blackout blinds. One of the highlights of a Christmas visit was a visit to the pantomime in Bath.

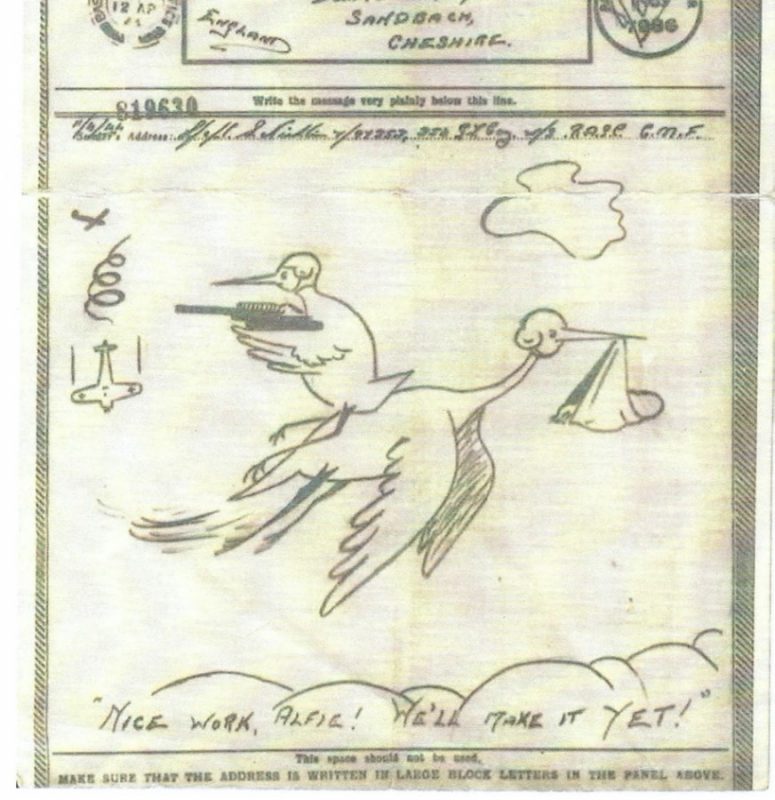

The church that my parents went to arranged dances and parties for American servicemen who were billeted nearby and on one occasion I attended. I can remember my father lifting me up and I was asked to pick the most handsome of a line-up of these soldiers. Some of them tried to bribe me with sweets but I resisted. I don’t remember who I chose. There were also Italian prisoners of war in the area who I think worked on local farms. Some of them made lovely straw baskets and I really liked the one I was given. In 1944 my brother was born. One of my parents’ friends was serving in the army and sent the aerogram pictured below. This friend had been at Dunkirk, but had survived and was still fighting in Europe when he sent the letter. Just before the war he wouldn’t get married to his girlfriend as he knew he was going into a dangerous situation; after some time had elapsed his girlfriend married someone else but he unfortunately was killed. After the war the original couple met again, married and lived happily together for many years afterwards.

My parents heard that the war was about to end in Europe just after I had gone to bed. I heard them talking about it to a neighbour and asked if I could join them as it was a special time, but they didn’t agree to my request. This was not the only time I missed out. I very much wanted to hear Winston Churchill speak from the train he was going to spend the night on at a railway siding near to our local station. One of my parents went to hear him but nothing was going to change my bedtime!