The 50th anniversary of VE Day on 8 May 1995 saw a variety of events in Radley organised by the Commemoration Committee. The Souvenir Programme included a series of short articles about people’s memories of the war. Five of these articles are reproduced below.

Joy Alexander (founder of Radley History Club)

I was busy being trained as a radio mechanic – by the elite of the services. Out of a class of thirty there were six of us who joined the Wrens and stuck together during our war service and after, but that is another tale.

This little highlight begins in London during the buzz bomb [V1 flying bombs] attacks. We were stationed at Hampstead and were bussed to Walthamstow for our training. So, we were bombed by day and night. All the other girls had no experience of air raids and bombs as they came from strange places like Glasgow, the countryside round Bolton, Cheshire and strange rural bits of England that I, as a Thames valley, near London, girl, knew nothing of. I had, all through the war been bombed, machine gunned, had shrapnel dropping from the sky and mundane other happenings and was used to ducking under tables, stairs and anything else handy.

But, back to the tale of the striped winceyette ‘jarmers’! The siren went again with the high-pitched wail – waaara – waaara – waaara. Mainly it was little men standing on a platform with a tin hat on, turning the handle like starting up a car, when cars had starting handles.

“Oh bother, not again. Shall we go to the shelter?”

“No I’m nice and warm here and if we hear the puttt-puttt-puttt getting nearer we can dive for cover when the engine cuts out.”

Unfortunately this wasn’t a puttt-puttt-puttt but a stray bomber, which had followed the Thames in from somewhere, got lost, and came in under barrage balloons – they were grey silk and located in the sky like big friendly piggies.

On the bomber came, suddenly there was a whishh-crump-crump-crump as it let go its load. This was followed by crash, bang and screams – at which point I sat up in my bottom bunk space shouting, “Everybody out”. I moved, nobody else did. The glass came in, in long thin slivers like knives; the building shook, dust rose, and all was followed by a dreadful silence apart from a little body clad in striped winceyette pyjamas sliding gracefully face down on to the highly polished linoleum floor and yells and screams from the next street.

Silence, then, “Oh dear, that was near”, came from the room behind me as I picked myself off the floor running lightly over broken glass like some Indian religious gent.

Sufficient to say not a foot not a head chopped off from my friends. A quick sweep of the broom and we all went back to bed. The next street was wiped out.

Jean Deller

Jean came to Radley as an adult to help look after her mother, who’d had a stroke. Her parents were then living in a cottage in Lower Radley. After her parents died she lived in north Abingdon but retained her connection with Radley until the end of her life.

When war broke out, I was living in Stanford-le-Hope in Essex. A friend and I were playing in the garden when the siren suddenly boomed out. We were terrified. My friend ran home and I ran into the house shouting ‘Daddy’. The house was empty so you can imagine how I felt. I sat on the stairs sobbing when suddenly my father came running in. He had been next door talking about what was going to happen.

I was just five years old. We slept in a shelter in the garden where I felt safe. I was evacuated for just a year in 1940 to Surrey, then went home to Essex. Occasionally we would visit my great aunt in Radley. That meant a train ride to London and then a train from Paddington to Radley.

Memories

- Of the houses that had been bombed in the road where I lived.

- Seeing large offices, a hospital and a church in ruins. The hospital beds were hanging out of the sides of the floors.

- Cakes and pancakes made from dried eggs.

- Helping my mother cut up marrow into small squares, adding pineapple essence, sugar and water to make a bowl of pineapple.

- Standing in the garden watching the doodlebugs go over. If the engine stopped, we lay flat on the ground.

- Sadness in our family as my second cousin in Radley was killed during the war. We all loved him and he is remembered on the war memorial in Radley.

- Happiness in school when the siren went – into the shelter to read comics and books.

- Fear was with me but we were taught to put on a brave face.

- Happiness when I was ten and the war was over. I hope it never happens again.

Radley during the war years was to me a quiet oasis. I loved visiting. There didn’t seem to be any fear. My aunts carried on as usual but Aunty Florrie who lived at 110 Lower Radley had an evacuee called Edwin. He was 13, I was 7 and I thought he was wonderful. He stayed until the end of the war and came back regularly.

VE day

I was woken up by my mother coming into the room and telling me the war was over in Europe. How happy we were. Flags were put out on the houses. Everybody was happy except that our neighbour was still a prisoner of war in Japan. We would not be happy until that part of the world was at peace.

Note: Jean’s second cousin, Leslie Ambridge Smith, was a sergeant in the Royal Artillery. He was killed on 28 November 1941 aged 36 at Tobruk during the North Africa campaign. His mother Mary and Jean’s grandmother Lucy were daughters of Charles Ambridge, the first stationmaster at Radley Station.

Ted & Ida Holst

Frederick Rasmus (Ted) Holst was born in 1915 in Sunderland and died in the Abingdon area in 1999. He married Ida Chapman in 1945 in Sunderland. Ted and Ida came to live in Ferny Close, Radley, following some years working abroad (we think Ted was a ship’s pilot in one of the Gulf states). Ida was very involved in several village organisations. A few years after Ted’s death, she decided to go and live nearer her daughter in the north-east of England. She still kept in contact with friends in Radley and liked to hear about what was happening in the village.

1941: Some mother’s son by Ted

It was a lovely August Monday in Canada Dock, Liverpool. I was gangway duty officer on the auxiliary aircraft carrier, HMS Audacity, awaiting orders for convoy duty with 36 Escort Group, commanded by Commander Walker, RN.

We had done all our practice and training, our aircraft were ready, we’d had our leave. About 14:00 hours a young seaman, designated HO (hostilities only) came up the gangway, hours overdue from leave. His excuse was that there was no train running from his home town, Sunderland, to Liverpool. Asked to repeat his excuse and to think carefully about his answer he again said that there was no train running on a Sunday afternoon. “First Lieutenant’s Report for overstaying your leave”, he was told. “But sir”, was the protest. “Unfortunately for you it is that you lied about the train. As I live in Sunderland, I caught the train that you said was not running”.

Days and weeks went by. On 21 December 1941, the battle that had begun a few days previously and was a running fight came for us to a calamitous conclusion. The Audacity was torpedoed and was sinking fast. I was on the flight deck, by the bridge sponson [a projection on the side of a boat, ship or seaplane], awaiting the final order, “Every man to himself” when the young seaman from Sunderland appeared beside me. “What are you doing here?”, I asked. “You heard the order to abandon ship”. ‘I can’t swim sir”, he replied.

He was wearing his Royal Navy regulation life belt, already inflated. I took him by the arm and faced him towards the blackness, and told him to start running as fast as he could without stopping. He did just that and disappeared over the edge of the flight deck into the darkness. I never saw him again.

Note: HMS Audacity, escorting Convoy HG-76 from Gibraltar to the UK, sank west of Cape Finisterre off Portugal in 70 minutes. A total of 73 of her crew were killed. Survivors were picked up by the corvettes, Convolvulus, Marigold and Pentstemon.

More about HMS Audacity

Keeping pigs by Ida

Some people kept pigs and fed them on collected kitchen swill. A licence was needed, but some people unofficially kept more than one. Permission was needed to slaughter an animal. The story goes that a farmer slaughtered two pigs. News arrived that an inspector was on his way. The carcase of one pig was hidden quickly. After the inspection the farmer’s wife asked if everything was in order. “Yes madam”, replied the inspector, “but unfortunately your pig had two left sides”.

Eating out by Ida

Towards the end of the war dried bananas arrived on the scene. They were revolting looking brown strips which swelled up in water.

Ted and I were having lunch in a hotel in the north-east. There was one other couple in the room at the time. On the menu were rice pudding and bananas and custard. I warned Ted not to ask for bananas but we heard the other couple ordering them. We sat in silence for their comments. Suddenly Ralph Reeder of Gang Show fame yelled out “What the b——hell is this?” as he looked at a dish of yellow custard with two long brown blobs in it. We nearly fell off our seats with laughing.

Wartime clothing by Ida

As the war progressed we used whatever came to hand. A prize was to obtain a white sack in which Canadian wheat was delivered. These sacks were of thick white material, which was great for tea towels, aprons, etc. Never mind the printed lettering which eventually bleached out.

Army blankets were made into coats and dressing gowns.

Ladies’ skirts were allowed three knife pleats. Coats no longer than 39.5 inches counted as children’s wear and so needed fewer coupons.

The backs of men’s shirts were made into aprons, tiny blouses, hankies and other things.

Hair was rolled around a stocking or a shoe lace. Legs were painted with liquid make-up and a black line added down the back of the leg. Aristoc stockings were very scarce and cost almost 8% of a week’s wage.

Gladys Williams: Using Radley Station in wartime

I first remember Radley Station in early 1942, when I was posted to serve at RAF Abingdon. In those days there was a waiting room with a cheerful fire. The train from Paddington used to stop at Radley and we then caught the Bunk to Abingdon and walked to the camp. When we had a 48-hour leave pass, a group of us would meet at Paddington, catch the last train at midnight to Radley which arrived in the early hours of the morning. By this time the Bunk had stopped running, so we walked through Radley to Albert Park in Abingdon. There we sat under Prince Albert’s statue to eat our sandwiches and then walk to the camp, sometimes to find an ‘apple pie bed’ waiting for us.

We were never molested or mugged while walking those 3-4 miles. Oh, happy days, wonderful companionship.

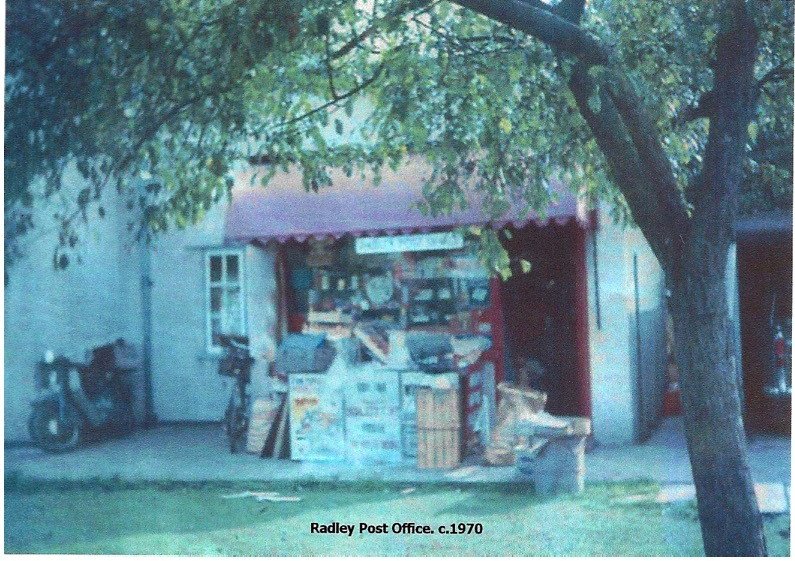

Twenty-five years later, my husband (ex RAF) and I and our two daughters moved into Radley post office and I spent 25 happy years in the village.

WW2 memories from Radley College: Experiences with the Home Guard

This article in the Souvenir Programme was an excerpt from the book, The Story of the First Berkshire (Abingdon) Battalion Home Guard by Ourselves, first published in 1945 [it’s still available in paperback]. The author is unknown but was probably one of the masters from Eastbourne College, which was evacuated to Radley College from the south coast. It is probably not a coincidence that its headmaster, John Nugee, had been Sub-Warden at Radley College before his appointment in Easter 1938.

On 28 June [1940] we [Eastbourne College] were evacuated to Radley. That summer we had two patrols each night in the College grounds. Duty came round every third or fourth night for officers and every seventh night for other ranks. The headquarters was the cricket pavilion and we had sentry groups on observation as far as a mile away, connected by field telephone. Orders were not to load except in an emergency. While I was at the furthest post, I heard a shot and at once hurried to investigate. I discovered that one boy of independent mind had decided that, if these times were not an emergency nothing ever would be, so he loaded and discharged his rifle at the Warden’s house, thereby bringing a committee of enquiry from the neighbourhood.

Another night I returned from visiting rounds to receive a message that a sentry had heard from the Warden that German parachutists had landed at Sandford Lock. It seemed very odd but one could hardly mistake one’s own headmaster so the picket was roused, sentry groups doubled and a recce patrol started. The atmosphere was tense – we did not expect half-trained and half-alarmed boys to last long against the Hun paratroopers. I investigated and traced the message to an observation post who had accepted this bogus message from someone who said he was the Warden. The observation post received a raspberry and the rest retired to bed.

Two nights later, long before we had any uniform, my second in command received an urgent message that ‘an armed band was at Chestnut Avenue’. Reserves were summoned and a strong patrol hurried off into the darkness, expecting to meet a sticky end. An astonished observation post eventually protested that all they had said over the telephone to a sleepy orderly was that they wanted their arm bands.

There were other great times – Sunday morning exercises spent in signal boxes, up gantries and under culverts until a worried station master urged that our troops should be protected from their more immediate dangers; cold nights spent on the Mansion roof spotting bomb flashes across two counties, and lastly those night patrols in Radley Park.